Yana Ross

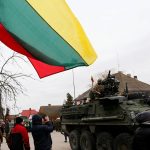

The militarization of Imperial Russia at the start of the 20th century when Chekhov was writing Three Sisters is uncanny parallel to our current frantic mobilization of NATO forces in Central and Eastern Europe as well as the Russian Imperial phantom pains on the border with Ukraine and the Baltics.

Chekhov was looking at the violent intrusion of the military force into civilian routine. He was anticipating World War I and the anxious mood across every class of a modern society.

We look at Central Europe political and ideological landscape and the shift to the intellectual apathy, so similar to Chekhov’s mood at the time of the play. Our Sisters are stuck in 2017 town of Vilnius and dreaming of Moscow or Bruxelles — and the army marching away towards Poland at the end of the play.

Three Sisters reviews 2017

“…Adaptation moves the play to our time: three sisters and a brother Prozorov are ethnic Russians who were forced to move to Lithuanian Socialist Republic in 1984 because of their father’s military service in Soviet Union. These sisters are much older than originals, they are between forty-five and fifty (actress Monica Bičiūnaitė, Vitaly Mockevičiūtė, Rimantė Valiukaitė) and are still connected to military – mingling with deployed NATO troops battalion. Stage design is a huge aircraft hangar, including impressive moving baggage belt, which carries many objects including weapons. A young scenographer Simon Biekšaitė, successfully continues to collaborate with Yana Ross, (Wunschkonzert, TR Warszawa); she moves the action from private Prozorov home into a kind of transit zone, area with a pool and dining tables, festive lights and fireworks. Hangar’s backwall’s live-media is designed by Algirdas Gradauskas feeds an omni-present eye of six surveillance cameras which switch from multi- to a single camera close-ups in moments of tension. When video goes black and white, it reminds us that all images once and forall will become historical and potential long-distance perspective is born: what is happening now, will soon be reviewed as historical evidence. Along those close-ups of military men celebrating New Year, awakens memories of a past world wars.

The final monologue shifts a conceptual focus from the sisters to a new character, Agnieszka Wersynska (in this adaptation a wife of lieutenant colonel wife) (actress Miglė Polikevičiūtė). The play about Versinina wife only hinted at, and the play it becomes an important character, which not only embodies the widespread society of Tipaza (called the man to the arts, popular spiritual theories and practices clichés suffused thinking and manners, is not sought dividing the left and right pseudofilosofinius tips) but also is a kind of the socium seismometer: mentally unstable, irrational, fragile Agnieszka his “spiritual I caught during (where any pseudo approaches and becomes difficult to be separated from archetipiškos god Silly assertions) near the many platitudes expresses the performance of important insights, and featured in the New year night bandaged wrists, ghost make-up and somnambuliška posture creates our aggressive, militant public offerings image. Actress Miglė Polikevičiūtė exactly feels and conveys his character’s duality, without losing (intervals macabre) humor distance.”

Alma Braskyte, Menufaktura

”In this performance, Ross radically deconstructs and reassembles the play, pushing it to the edge of the 21-st century and the edge is not only geographical, the edge of Europe or the world, the borderline is also symbolic and full of linguistic tension. There are none of the usual “Chekhovian” tones or cliches— everything is adjusted to reflect the moment in time. Ross is considering the responsibility of parents for the fate of their children and vise versa but it yields no sympathy or blame from director, objective, pragmatic and critical stance. […] The military here is multi-national, representing NATO forces and able to communicate among themselves in broken English, German and even Polish, but what unites them most is the constant games (literally and figuratively, the theater of war) which they perpetually play. Games are the substitute and hide latent aggression and readiness, mobility. The sisters are not young or naive— these women, in their late forties, are capable of reconciling with their fears and mistakes, hopes and failures. Masha is drinking herself to death, Irina slaves away in the kitchen, and Olga is most likely responsible of pushing her younger brother into hastened marriage, just to get away from this triple “mothering.” […] Instead of the long final soliloquy about hope and salvation through labor, director once again (as with her earlier Chekhov productions) turns to the theme o self-destruction. Baron von Tusenbach does not lose his life in a duel, he does use the pistol, facing the trigger himself. Suicide is a brutal ending, but nonetheless Chekhovian to the core.”

Nina Karpova, Theater Journal

[…] one has to remember that Chekhov rote this play while spending his summer in Crimea, part of the Russian Empire at the time. It is crucial for Ross to reflect upon political implication of Russian expansion, specially since Crimea has been annexed by Russia, once again. Not many directors (except for a few in Germany, perhaps) who turn to dangerous and volatile political context, but for Ross it has become inseparable context for most of her performances.”

Thomas Irmer, Berliner Freitag

Premiere March 17, 2017