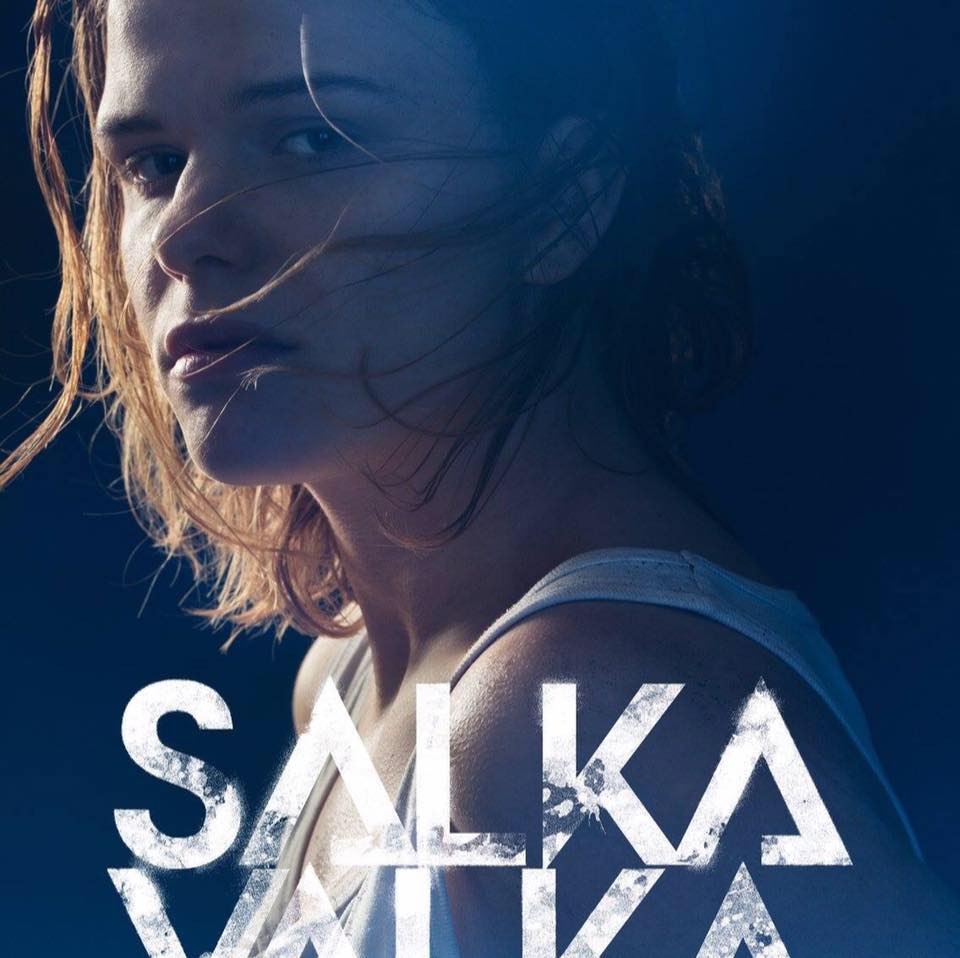

Yana Ross

Nobel Laureate Halldór Laxness classic novel from 1930’s Salka Valka is being challenged, probed and adapted to question modern Icelandic society. Iceland’s recently history includes a seismic financial crisis, volcano explosion and tourist boom. But recent confidence is crushed again by Panama Papers scandal implicating most of the ruling elite in a massive financial fraud suggesting a deep brake within the tight-knit society. This new production is also challenging writer’s gender-bias and political ideology through a modern frame. By staging it as a process of independent filmmaking, director and her team are deconstructing classic cliches and building direct dialogue about current state with the audience.

Laxness originally wrote Salka as a script for a Hollywood film, imagining Gretta Garbo in the leading role. This bridges the original treatment with an adaptation and invites the audience to look at Laxness from here and now, and without revery or a pedestal.

Excerpt from the adaptation:

Why did you decide to make this film?

Halla (film director): I was angry. I was angry that our society is so conservative, so narrow-minded and so much resembles the heard of sheep (which is by the way a good skill we are starting to lose as a nation) in this blinding revery for this pompous misogynistic male voice. It is time to re-evaluate this classic in the context of contemporary world society and see if his statements are still valid.

And what are the means of doing that?

Halla: We can question the sensationalist tools he has used to attract the reader. The classic sexual and erotic tension, the intellectual and physical dominance of male heroes over a simple but strong female. How much does Laxness dwell on the swollen, red and moist Salka’s limbs when she’s confronted with Steintor? She’s always gasping for air, clearly aroused by his body hair, sweat and violence. How dare we propagate the rape culture into the 21st century? How long will it be ok to portray the sexual violence on film and on stage to excite the box office thrill? The audience loves a good rough fuck! The audience will be wet with empathy over a shriveled Salka in the corner of her hut holding a knife but week in her knees.

Do you think he was aware of what he was doing?

Halla: Laxness was a clever man. He had an enormous ambition, somewhere between Falstaff and Macbeth, his soul was trapped in all-consuming desire for fame and fortune. He dreamed of being famous. Of Hollywood glamor, of international publishing, money, travels and luxury good. A sober cynical brilliant talent, he surely knew how to get it. All the possible sensational tricks of the trade wrapped up in unique and powerful literary voice— here’s a recipe for you!

What about the form for your feature?

Halla: It is no secret I admire Lars von Trier. We come from the same film school and were part of Dogma for a while together, so I don’t think it is any surprise that I keep experimenting with form, just like he does. I am interested in blending borders between acting and living, between staging and filming and sometimes it creates incredible tension on the set but I don’t see any other approach.

Is this tension bringing you closer to the truth? About the film or yourself?

Halla: Yes.

Are personal relationships unavoidable in such environment? You are notorious for blending your personal and professional lives as well…

Halla: I don’t plan it, or crave it, if that’s what you’re asking. All I care about is being true to my film.“

Salka Valka reviews 2017

“Instead of wasting energy on recreating a well-known book, or following conventional story-telling, Y. Ross, S. Guðmundsdóttir and entire ensemble decide to share with us thoughts and process ignited by novel. The result touches the intellect, raises goose-bumps and waters the eyes. This performance is not replacing the book, it proves to be powerful and independent, made by people with strong will.”

Þorgeir Tryggvason

“Deconstruction is an interesting performing arts tool, but not in our Icelandic theater. It must stop. Sad to see the audience miss out on the change to feel deep emotions and passions of our beloved characters. Classics should give focus to human emotions. And there’s little room for it here.”

Sigríður Jónsdóttir

A journey through time

“In Reykjavik, a strong direction by Yana Ross transposes a century-old novel of Icelandic literature into a panorama of the modern state after the banking crisis.

Halldór Laxness is one of the great European writers who have measured the twentieth century with all its’ aberrations and tragedies, leaving a work that allows us to look at the present as well. Laxness (1902-1998) received the Nobelpreis in 1955, but above all for his novels which follows the changes of Iceland. This includes “Salka Valka”, published in 1932, which tells the story of a young girl in a small fishing village at the beginning of the last century, turned from a fierce existence in a world full of violence, abuse and social backwardness into a self-assured businesswoman.

The novel shows vividly how modernity engages in a small society: a fish factory produces paid work, its owner, merchant Bogesen also runs the only shop in the village. Thus, progress has its price – Laxness makes a parallel with the developments of his time, the creator of political disputes about the social conditions. What at first glance looks like a political developmental revolution is fundamentally multifaceted and even deep psychological profile of interrelationship between poverty and humanity.

The fragility in the process of modernizing Iceland is reminiscent of the great banking crush of 2008 for 337,000 inhabitants – the worst of world history. Thanks to Laxness’s Nobel Prize, Iceland can lead the world’s largest Nobel Prize laureate per capita.

“Salka Valka” in the version of the Lithuanian-American star Yana Ross is above all a perfect example for the Ross-signature talent in merging past and present. The impetus in the staging is an independent film adaptation which allows director to probe the validity of the novel in current political and social climate. Ross shows the dangers and humor of mass tourism that has been artificially forced after the crisis, renewed corruption of Icelandic institutions in international affairs such as Panama Papers.

Polish stage designer Michał Korchowiec creates a vast post-industrial space which is dominated by a skeletal sculpture, eminds of a collapsed factory roof. Underneath the sculpture is a series of benches, the formation of which recalls a church. A free associative space on the edge of which is a sound recording booth for the well-known voice over of Gudni Kolbeinsson. His voice narrates between the scenes the strong passages from the novel, giving the audience a chance to savor the original prose language. Behind it, there is also a modern hotel room for the Film crew to rest.

Their occasional penetration into the actual Salka story is so brilliantly plotted and organized that it never loses its intensity.

It is above all, Blær Jóhannsdóttir as Salka, which captivates our breath: A woman who can not be confused in confused times. The opposite: the traumatized girl she once was, is literally portrayed by a child actor, allowing the powerful associations to run wild regarding taboo of child abuse and paedophelia in Iceland.

Director not only understands how to compensate the complexity of the novel, but also to expand it. When the giant Bogesen (Jóhann Sigurdharson) makes everyone leap over his heavy cane, the several pages of the book are played in front of us with great imagination and versatility of masterful directing and the scene continues to expand with contemporary tourists flooding the stage with their cameras and selfie sticks surprising early industrial characters who were still struggling with modernity.

The historical Salka from Laxness’s time of the capitalist modernization breaks into a journey into the present, with Yana Ross always keeping this classic of the literature at its core. The director developed the idea of the filming on stage from the fact that Laxness himself in 1928 in Los Angeles wrote the 5-page script of this quasi-allegorical figure for a silent film (“A Woman in Pants”). Greta Garbo was, according to his letters, about to play the part. The germ of the novel was thus a never-realized film script from the time before the big stock market crash in America. A factual and associative network that seems to have made a successful match for Yana Ross’ ambitious epic work.”

Thomas Irmer, Theater der Zeit

Premiere December 30, 2016